Reading time: 10 mins

I like hard solitaire games.1 They seem to jack directly into the part of my brain that manufacturers reward chemicals. It’s also nice that there is no deeper meaning to analyse, complex plot to follow, or involved mechanics to master. As a result I’ve been playing The Zachtronics Solitaire Collection on and off for a good while. Zachtronics were a game studio that (mostly) made puzzle games. Starting in 2016 with Shenzhen I/O each new release contained a new solitaire mini-game, which eventually culminated in the release of the Zachtronics Solitaire Collection in 2022. As you can guess, it’s a collection of their different patience games.

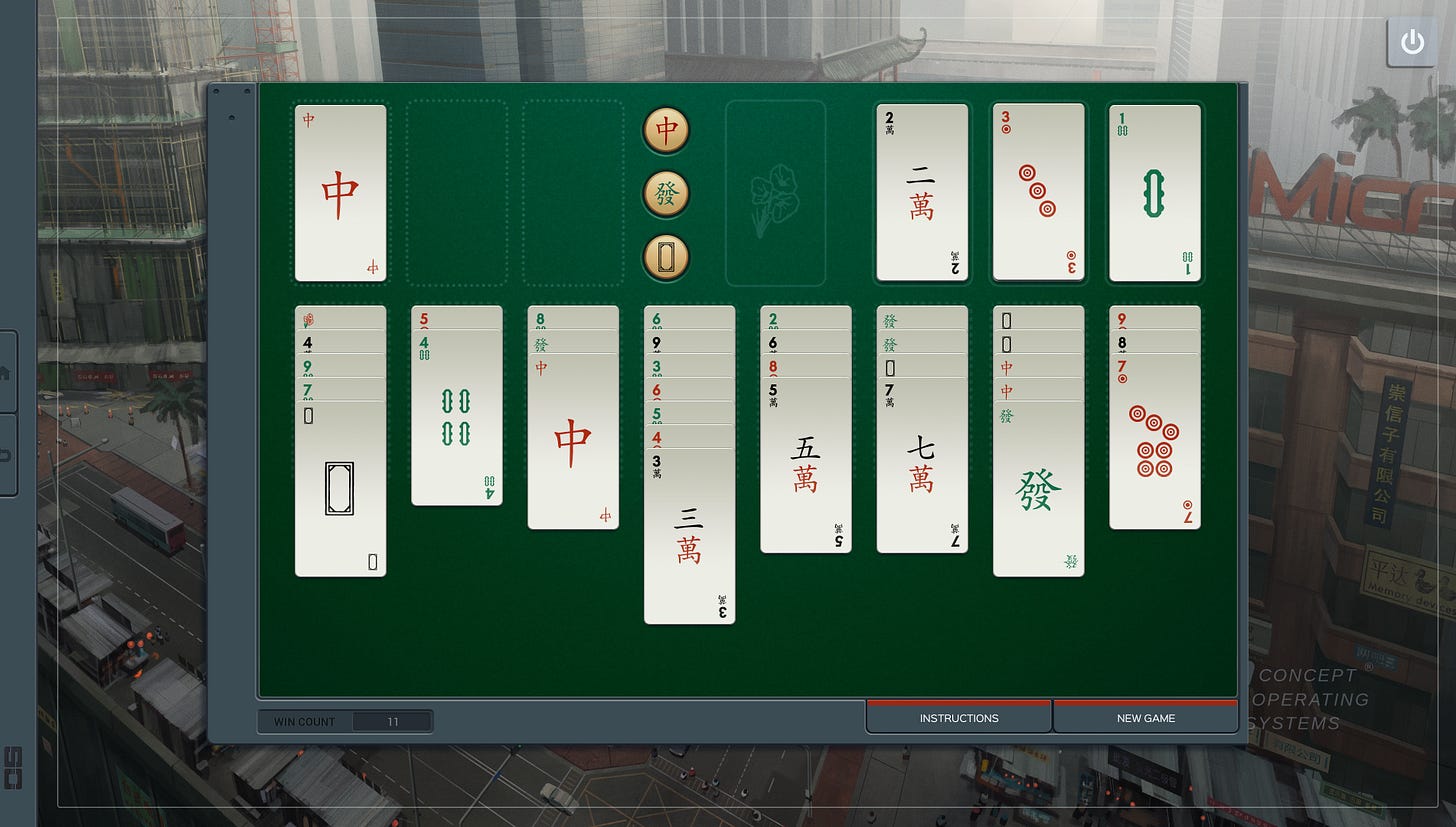

Chronologically first is Shenzhen Solitaire, which shows its age a little in the graphics compared to the later entries. The sounds are a little sharp for my taste, the cards slicing through the air like digital razors. The backing music sets the stage for the rest of the collection, low-key chill beats that help me focus on solving the puzzle in front of me. It uses three suits of nine cards inspired by majong tiles, with three sets of four dragons and one flower – the goal is to move cards to the foundation, but they can only be stacked in descending numerical order of alternating colour while still in play. It’s really a great take on solitaire, taking a little more thought than the standard patience that I grew up playing but not so much it becomes frustrating.

Shenzhen Solitaire is attached to Shenzhen I/O, a puzzle game about building electronic circuits for devices. In Shenzhen I/O the player uses the simple programming language present in the previous title TIS-100 (and later in Exapunks) to create automation by writing micro-programs, which are then used as part of a circuit board to solve puzzles. In my opinion the coding elements successfully walk a fine balance between simplifying the scripting process while still retaining the aesthetics and evoking the right emotions; I know well from my day job that scripting involves confusion and frustration when something doesn’t work, then a brief rush when your code finally starts working right. I never did finish Shenzhen I/O, running into a difficulty wall that made me drop off, but overall it is an interesting, and I think satisfying, puzzle game which I do recommend.

Exapunks is another programming game, where the player writes micro-programs; this controlling tiny robots to complete increasingly complex tasks. These are all phrased as hacking, starting simple with targets like banks and escalating to copying the human mind. Exapunks has probably got my favourite visual design of all of the Zachtronics games, and I love that the manual is in the form of a diegetic zine owned by the player character. In this case I got to the penultimate mission before hitting a difficulty wall, and I would like to go back and finish it off at some point. This is a theme for me, seen also in not quite having finished TIS-100 or Infinifactory (I’m on the last puzzle in both cases). For me, the depth of complexity means that I find it daunting to jump straight back into late game puzzles once I’ve spent significant time away from the game. I will say that the games do a good job of slowly building up mechanical complexity for the most part.

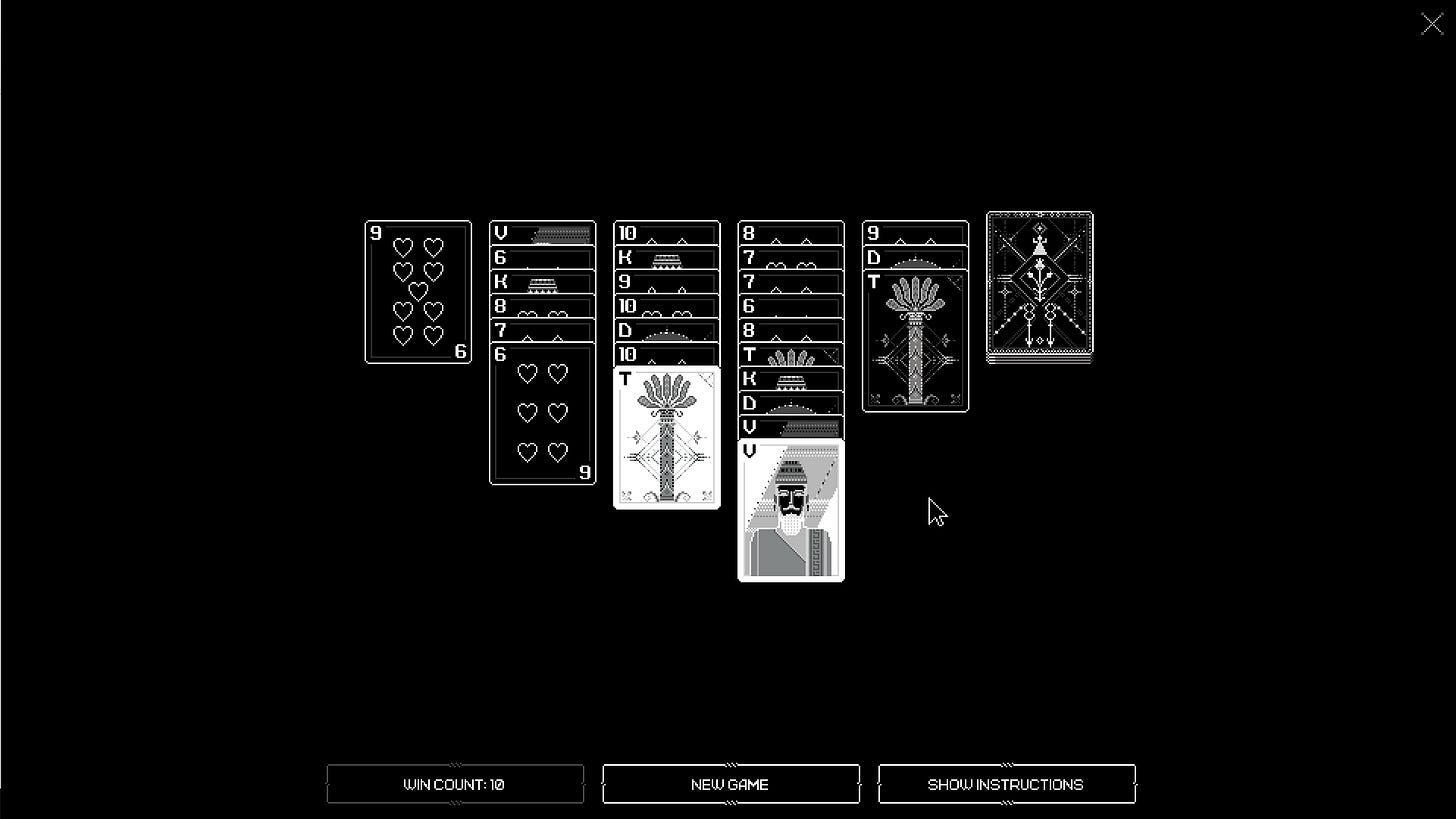

The solitaire variant of Exapunks is Proletariats Patience, which 100% has the best music in the collection. The aim is to “organise the proletariat, while the aristocrats gather their families and escape”, which is done by stacking numbers cards in alternating colour and decreasing value while putting face cards together into suits. It discards all of the cards below six, and is straightforward compared to some of the games in the collection. That said, you can back yourself into a corner if you’re not paying attention. I dig it.

The most straightforward game in the collection is Sawayama Solitaire, which is basically just the patience you’re thinking of right now. In the words of the Zachtronics Solitaire Collection it is “classic Klondike”. It is remarkable for being the only game in the collection with hidden information, in the form of face down cards. I really like the visual style of this one, with some very nice pixel graphics, but the incessant loop of low-bit midi music drives me to distraction. I can still hear it now, the minotaur’s growl in my own personal Navidson House. The game it is attached to is an odd one, in a good way: Last Call BBS is a collection of smaller puzzle games, themed around the player loading up a retro-computer. I’m too young for the nostalgia I’m sure the developers intended, but for me it does strongly evoke the feeling of messing around with micro-computers. Of the mini-games, 20th Century Food Court is my favourite, where you automate robotic food production lines; it also contains programming, in the form of physical computing by wiring together modules in a server rack. It has a good sense of humour, my favourite joke being the puzzle where you serve Coke and Pepsi from the same machine, but have to paint the cups to indicate which drink it is. ChipWizard Professional and X’BPGH: The Forbidden Path continue with twists on the concept of physical computing; while Dungeons & Diagrams, STEED FORCE Hobby Studio and HACK*MATCH all also exist. I enjoy them less, but lucky for me Last Call BBS also contains a “retro-demake” of Kabufuda Solitaire.

As I write this paragraph I am installing Eliza, the lone visual novel from Zachtronics, so I can play Kabufuda Solitaire in its native environment. Up until this point I’ve only played it in the demake and the version included in the Solitaire Collection. It’s the only game in the collection with difficulty levels. These affect how many free spaces you get to work with – if you play it on the expert difficulty it’s very easy to back yourself into a corner if you don’t look ahead to how moving a card will affect the board in turns to come. It’s a sorting game, where each suit of four cards has to be bought together. The designs of the cards are particularly nice, and as an aside it turns out to be quite difficult to buy a deck of kabufuda playing cards where I live in the UK. The sounds of moving cards are nice, little mechanical clicks meant to indicate tapping on a phone screen, but the subtle background music isn’t to my taste. But, having now played a chunk of Eliza, I can confirm that the relaxed audio of Kabufuda Solitaire works much better in the context of its parent game.2

Silence, the most relaxed form of audio, is why I don’t enjoy Cluj Solitaire. There is no music, only a raw ambience of wind and distant rail freight. This matches the stark aesthetic of Cluj’s parent game, Molek-Syntez. I find Molek-Syntez less difficult than Cluj, completing most the main puzzles in about five hours while catching up on some podcasts. Perhaps it is because I’ve spent years starting at chemical formulae but the central premise, retrosynthesis of organic molecules, came very naturally to me. Control of the molecules is via six particle beams around the edge of the hex-tile game area, with their functions automated via a simple visual programming language. This lets you snap bonds, rotate fragments, and do all kinds of chemistry that I wish were so easy in the real world. I do have a minor gripe, as in one early puzzle I found out that the game does not view the two resonance structures of benzene as equivalent (which they are, chemically speaking). I also thought the puzzle mechanics were quite straightforward, with only a few of the main set of puzzles giving me significant difficulty. It may be that the devs thought this too, as the number of puzzles is doubled by a set of harder molecules. As to the story of Molek-Syntez, it is a very light presence and I have no strong feelings about it beyond enjoying the desolate vibe.

Cluj has the most minimalist design, rendered in black and white pixels. The game uses a Russian style deck of cards where ace through king are rendered as T, K, D, and V, so there is a little work expected from the player if they’re not familiar with this style of cards. The game is simple sorting, from T to 6, but there are no free spaces. Instead you can cheat by putting any card on any other, locking that stack until you put the card into the right place. As solitaires go it’s quite good, but it’s overshadowed in all aspects by the other games in the collection – especially as it is “more about luck than skill.” It’s not one I play for fun.

On the topic of luck, Möbius Front ‘83 has a fatal flaw – randomised damage. The premise of the game is to fend off an invasion of America by an alternative-reality America, in the form of a turn-based strategy game. Gameplay involves moving units around a hex-tile board, utilising the environment for cover and various unit abilities to destroy enemy units. I love this concept, and the music and visuals carry it well, but randomised damage output keeps the game from greatness. As most units do random damage within a range you can’t be sure of their damage output, making it impossible to strategise aggresively; the M1 Abrams main battle tank does 2-6 damage, which could be a one-shot kill if luck is on your side. The flip applies, where getting caught out in the open can have your unit wiped by one unlucky shot. It encourages very careful, conservative play, where risk-taking is harshly punished. Low-key I felt like I should play most missions once to find out the lay of the land, then a second time to actually win it by making sure I overpowered each foe with an unholy volley of fire from several units at once. I did still finish the game but a minor mod to remove random damage would do wonders. Luckily it has one of my favourite solitaires. Cribbage Solitaire deals the deck out into four face-up piles, and the player has to draw cards to a total of 31. Points are scored for various combinations: starting a trick with a jack, getting 15 points, drawing cards in numerical order. It rewards planning and consideration, and on top of it has background music that suits the military theme of Möbius Front ‘83. I also like playing cribbage now.

You might point out that Möbius Front ‘83 isn’t that much like the other games in this essay, but I would counter that Cribbage Solitaire still uses a deck of cards. Sigmar’s Garden does not. This solitaire is really just lovely. It’s an alchemical themed matching game where you remove marbles in pairs from a hexagonal board based on simple rules – the four elements are taken as pairs or with salt, vitae and mors are always taken as a pair, and mercury eliminates the metals in a series from lead to gold. The graphics and background music are delightful, very low-key and chill. It’s probably the easiest game in the collection, but very fun as a result. I could zone out and play it for hours.

Sigmar’s Garden is a great fit for its parent game Opus Magnum, like aqua regia in a conical flask, where you create alchemical machines to transmute lead into gold and other such mundanities. Opus Magnum is one of the few Zachtronics puzzle games I’ve finished, and it’s also a delight. It has a fun story about a noble house being brought low, the broad outline reminding me of Herbert’s Dune for some reason, and really well themed puzzle mechanics. The player is given a field of hex tiles on which to place mechanical gizmos to manipulate small molecules, breaking them down and building them back up. It’s similar to the concept behind Molek-Syntez (and the earlier title Space Chem), but shows how much the theming of a game can elevate it despite similar mechanics. That is, I like Molek-Syntez but I love Opus Magnum.3

The last game is unique to The Zachtronics Solitaire Collection, and is my favourite of the whole solitaire cadre. Fortune’s Foundation is a patience game using a Tarot deck split into fifty-two regular playing cards making up the minor arcana, and twenty-two cards in the major arcana. The goal is to sort each suit in foundations numerically ascending from ace to king, and cards can only be placed numerically ascending or descending by suit. All cards are dealt face-up into 10 piles, and aces are moved to the foundations during the deal. The playing field starts with one free space. Only one card can be moved at a time, and the foundations can store one card at the cost of blocking new cards from being added to the foundations until the stored card is returned to the board. In Fortune’s Foundation the major arcana follow the same rules as the minor arcana except they are played to their foundation in both ascending and descending order, meeting in the middle.

This is the whole game, and the difficulty comes from the sheer number of cards and limited movement options. There is no hidden information, so the player has to think several moves ahead to make sure they do not commit to a course of action that leaves them stuck. At the start of a hand the field looks impossible. Fortune’s Foundation also lends itself to choice paralysis by virtue of being able to stack ascending or descending values. That is, each possible move comes with a corollary; stack 6 on 7, or 7 on 6? Both moves can have several follow up moves, each of which splits in the same way. There are only a few routes through this branching path, and moving the wrong card will lock you into a course of ruin.

Aside from the challenge, which does become routine as you learn how to play, Fortune’s Foundation is carried by its presentation. The tarot cards use bright colours and bold shapes to preserve readability while keeping the playing field interesting to look at. The best part is the original soundtrack, “Fortune’s Foundation” by Matthew S Burns. It is a low-key cosy song that is unobtrusive, but helps me focus on the game. The track loops as you play, but at nearly 8 minutes long and with plenty of variation within that I find it doesn’t outstay its welcome.

If pressed for an opinion I would say that anyone with a passing interest in solitaire will get a lot out of The Zachtronics Solitaire Collection (and Fortune’s Foundation in particular). A strong part of this is the commitment to theming the mini-games to fit in with the parent games – the silent audio-scape of Cluj solitaire, the pristine pixel art of Sawayama Solitaire. I also think that on some level, the devs realised that solitaire itself is a kind of a puzzle. The games then provide respite from the more difficult challenges provided by the main games, a relaxing garden where the player can reset by engaging with a problem they essentially already know how to solve. Given that daily life can be complicated in so many way, it seems obvious to me why an occasional game of solitaire appeals.

This work is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

Yes I also enjoy Balatro.

Stay tuned for more thoughts on Eliza.

I once received an email from a work colleague who had misspelled the phrase “magnum opus” as “opus magnum”, and having played Opus Magnum this made me chuckle.