What do you want to do with your life? Is it a simple question? In my case the answer was *radio static* for a long time before settling onto “scientist”. The process of getting there felt more like something that was happening to me than the execution of a well-designed plan, and I felt that sense of falling through life very strongly while playing Eliza. While the game spirals out from there into an unflinching look at the intersection of social and personal issues with technology, especially mental health and the role of tech in healthcare, the bedrock of the story is about finding your way.

Spoilers for all of Eliza. Go play it.

Eliza follows the aimless Evelyn Ishino-Aubrey as she re-enters Seattle society after a serious bout of depression. She’s done a little work at a bookshop over the past three years, but mostly just existed. One Monday, she walks into an Eliza Proxy centre. This is an artifical intelligence (AI) medical centre, which uses people as the mouthpiece for highly the advanced therapy software Eliza. It’s later revealed Evelyn had previously worked for the parent company Skandha as one of the software engineers who developed Eliza, but the tragic passing of her close colleague led to her withdrawing from her life.

Evelyn has very little family. She’s in email contact with her mother, and her dad is estranged somewhere in Japan. She has fallen out of touch with her close friends, and doesn’t seem to have much in the way of hobbies or interests. While some of this is a symptom of ongoing depression, I get the strong sense that Evelyn is one of those rising stars who are liable to burn out. She’s established to have been a talented programmer, getting work at tech giant Skandha right after graduating university. It makes me wonder if she’s ever had room in her life for herself, or if she’d been locked on to her career so hard that the rest fell away. With her job no longer viable, she was left with no direction and no distraction.

Walking into the Queen-Anne Eliza Center, Evelyn meets Rae. She’s a low-level manager for Skandha, but she’s truly warm, a people person. Rae is also straight-laced, comfortable within the system she works in. Evelyn’s first session as an Eliza proxy goes poorly, the client becoming agitated and giving her a real scare, but Rae is present to console Evelyn that she did all she could. Evelyn’s first thought is that, hey, can’t we do more for that client? Surely he need some more help immediately. Rae firmly encourages Evelyn to trust the system, and not deviate from the Eliza treatment program. We later discover that Rae has been dealing with her problematic brother for years, and is keenly aware that pouring all of your resources into one person can just burn you out without helping them. Rae is aware of the shortcomings of Eliza, but she is willing to accept them as the cost of providing accessible mental healthcare to as many people as possible.

Later that day, Evelyn meets with her old co-worker Nora. Where Rae is warm, Nora is ablaze. She was also a software engineer for Eliza but cast it aside after the death of Damian, unable to breathe tangled up in the corporate system. She now works as a musician and artist (stage name Li’l Sappho), keenly politically active. You could view Nora as selfish, but I think she is centring her life around herself after years of sacrifice for others – similar to Rae. From Nora, Evelyn is exposed to the concept of striking out by herself. She is encouraged to do whatever she feels like doing, be it working for Skandha or becoming a politically active artist, as long as she chooses it for herself.

Nora gives the plot the last kick it needs to get rolling, by getting Evelyn to attend the OneMind tech industry conference later that week. Here she hears her old boss Soren Lloyd-Rose talk about his new spin-out company, and runs into the CEO of Skandha Reiner Tsai. Both want Evelyn to come to their companies as chief engineer. Soren wants to end human suffering – he’s in pain, and his company is developing a technology to sooth any hurt via induced dreaming. Reiner wants to develop Eliza further, into a general artificial intelligence.

From here the plot of Eliza is kept at a steady boil. Glossing over a lot of details, Evelyn is held in tension between her past and the branching futures laid out before her as the core cast present her with conflicting ways to live her life. Rae and Nora show her that there is more to life than work; Nora makes music and Rae bakes cookies, both living for themselves in their own way. Evelyn is keenly aware of mental health and can’t deny the possible benefits to humanity if she goes back to Skandha to develop Eliza further, or if she throws in with Soren’s new company Aponia. Her past life haunts Evelyn too, represented by the young Skandha software engineer Erlend. Throughout, the game shows Evelyn the realities of the lives she could live; for example Skandha accidentally leaks Eliza patient data, and Eliza therapy doesn’t seem to help its clients overmuch.

There are several endings. Evelyn can step back into her old life by becoming the chief engineer of the Eliza project with Reiner. In this ending Evelyn gets her only costume change, swapping her comfy hoody for formal office clothes. She becomes colder, fully commited to her work. In Nora’s ending, instead of becoming cold and detached Evelyn feels a wild fiery joy – her future is uncertain but she is living for herself. She’s taken steps towards becoming an electronic musician, and her future is wide open. Under the influence of Rae, Evelyn chooses to help people by becoming a therapist. This ending is warm and comforting, where you can be sure that Evelyn will take future challenges in her stride. Meanwhile, if Soren and Evelyn work together they succeed in producing a device that can remove pain. Evelyn begins wearing it regularly at low power, numbing the bad parts of life enough that she’s more focussed and productive in her work. She seems happy, as though she’s washed her troubles away with opioids.

There is a fifth option for Evelyn. She can choose to leave Seattle behind, dropping the tangled threads linking her to the city and its tech scene. This is the most melancholy outcome, as Evelyn is left optimistic but facing an uncertain future. She breaks ties with her past via a brief conversation with Erlend where it becomes clear that everything in Seattle will tick along without her present. This ending contains the infinite potential of a life begun anew. In her own words, “Now I am nobody. Not necessarily in a bad way...”

The key thing that spoke to me about these pathways is that they all work for Evelyn. She’s making an active choice for her own reasons. It might be a dumb choice – the ending where she makes Eliza into a general AI doesn’t ring true – but the primary focus is on Evelyn and her life. The second broadside the game delivered to me, off-hand, was when it mentioned in an early scene that Evelyn kinda fell through life from undergrad to post-grad to Skandha hotshot, before suddenly realising she was in her thirties. If she could have her time over, would she follow the same path? The end of the game gives Evelyn this chance to evaluate what she actually wants, and even if she takes a step back into her old career, she chooses it for herself.

Eliza is a game I’d recommend almost anyone to play. It’s deceptively simple, but it contains great depth. I wasn’t able to break open and talk about most of the themes present in the game, barely skimming the top of mental health and only mentioning the others in passing. Maybe another time. However, the core of Eliza remains experiencing Evelyn’s struggle to find her way through life. The game shows the player that even when things are at their worst, you can recover and find a way through life. This isn’t sugar-coated with neat endings and easy choices, but Eliza tells us that with space to grow and people to support you, you can find your way.

Gameplay

Eliza is a visual novel.

No, but, mostly the gameplay is reading text. The first flavour is conversations, which make up most of the game. The player gets occasional input to decide what Evelyn says, typically either agreeing with a statement, challenging it, or offering an alternative viewpoint. There are also occasions where your choice can result in slightly different information being revealed about the world. That is, your input has a relatively small impact on the course of the game, and doesn’t change any of the major plot events. In the words of Burns, “...have you ever been talking with someone and it seems like no matter what you say they say what they were gonna say anyway.” [1] From a utilitarian perspective the “gameplay” here is lax, but again Eliza is a visual novel and as far as I’m aware this is the de facto experience for the genre. I found the best way to approach this part of the game was to engage with the conversations emotionally, choosing dialogue options based on how I felt rather than trying to meta-game the outcomes. This makes the game into a radio-play, and I found it very easy to let it wash over me (but then, I am a fan of radio-plays). Between scenes the player is often allowed to interact with some environment elements for greater world info, clicking on highlighted items to hear Evelyn’s thoughts about them.

There are a variety of language options, but as far as I’ve tested the voice acting is always in English. The pause menu has a History option, which lets you read back through conversations that have already happened. I liked using the auto-play feature, as the conversations can be quite long and there can be some time between dialogue choices.

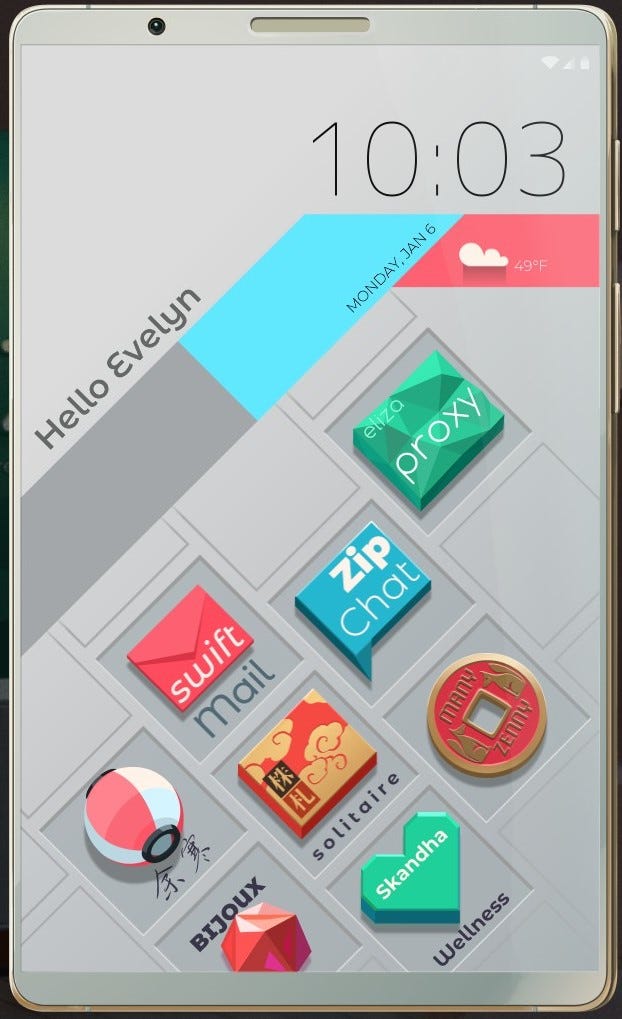

At any time during a conversation, you can whip out your phone to check your messages. This pauses the conversation at the last spoken line of dialogue, and feels like a cheeky poke at the ubiquitousness of smart phones in modern society and the current etiquette of when it’s okay to check your dm’s. Evelyn’s phone has a few apps. Zip Chat is an instant messaging service that is used to carry on conversation with the main cast. This sets up later events, such as Evelyn being invited to Nora’s gig in the first chapter, and allows a second route for characters to get across their world-view to Evelyn and the player.

Swift Mail is an email client that adds greater world context throughout the game. During Chaper 2 when Evelyn voices concerns over Skandha’s privacy security, she receives two emails – the first is from a contractor Skandha has engaged to collect survey data from Eliza proxies, shortly followed by a second from Skandha, explaining that due to a data breach anyone who took part in the survey may have had their private information exposed. Clearly the emails are used to reflect the concerns of the main cast, and giving the player world-building context to help them decide who they agree with. Is a data leak a big deal, or is it the price of business in the modern world?

Eliza Proxy is used by Skandha to coordinate its proxy contractors. It contains a separate email, a work email to the personal Swift Mail, used to distribute information about Skandha’s operations and corporate culture to the player. As well as this, it contains the ratings given to you by your clients, your “Proxy Level” and “Proxy Rating” (the rating of Eliza proxies by their clients, later revealed to be normalised to stop anyone getting too far ahead of the curve), and badges for achieving specific goals as an Eliza proxy. The badges are typical gameificaiton of work, like receiving a 5-star rating or getting a new client, which the player has no control over. Eliza Proxy serves to deepen the concept of Eliza therapy sessions for the player, creating a coherent world for the story to take place in.

The other apps play a supporting role in establishing the tone of Eliza. Evelyn has a wellness app called 余寒, which I am going to tentatively translate as “Lingering Winter” as this is the title of the track that plays when the app is opened in game (also, Leigh used a Kanji dictionary). I still don’t speak Japanese, so grain of salt. This app updates periodically throughout the story, every other chapter, containing a relaxing (melancholy?) image and a brief piece of open advice. The first screen shows a string of lanterns hanging at dusk in the depths of winter, with the phrase

“Think back to what brought you here.”

The second is a picture of a person standing on a bridge with their back to the viewer, looking across a river toward a nighttime cityscape. Lights twinkle in the distance under the phrase

“There’s no need to rush.”

In the last chapter, the app shows two people sitting at an izakaya at night, footsteps in the snow and steam rising from the cooking. Above them

“Who is important to you?”

These are of course deeply relevant to the events of the main story; tracking Evelyn’s journey from feeling aimless and adrift, through developing her connections with the people around her and immersing herself back into the world, and finally prompting her to decide what she will dedicate her life to at the end of the game. As an actual app, I’m not sure what 余寒 would be. Perhaps some kind of daily or weekly motivational quote? As far as I recall, I don’t think this app is ever directly referenced by Evelyn, it being optional if the player ever opens it. Its utility to the story of Eliza is obvious however, and that’s something I like about the game. For all of the complex issues involved, Eliza presents its themes directly to the viewer.

Kabufuda Solitaire is the obligatory solitaire minigame found in most games from Zachtronics. I’ve discussed its mechanics elsewhere, but from a narrative perspective it helps reinforce Evelyn’s clear desire to know more about the Japanese side of her family, and provides a safe space to retreat to for Evelyn when the world gets too real. It is a calming, simple game that still requires some thought to play well, and has a soothing ambient soundtrack that’s fitting for the themes. This is actually directly referenced by the game in an email from Meredith M. Mercer, an old acquaintance of Evelyn’s who she seems to be in occasional contact with; (paraphrasing) Meredith comments that patience games are like life in that what seems to be the easy path forward can actually result in you getting stuck, and some careful thought should be applied.

The remaining apps are set-dressing. Bijoux and Many Zenny are games Evelyn has lost interest in, Bijoux seeming to be a pun of Bejewelled, and Skandha Wellness is the app Eliza clients are referred to for some of the wellness activities Eliza suggests in therapy sessions. I particularly like the inclusion of Skandha Wellness, as it helps show how ubiquitous Skandha have made themselves in the health world.

A brief tangent about the phone. It has a prominent clock that updates in real time, allowing you to compulsively check the time if you’re into that. The hour helps set the scene for any given scene, indicating that time has passed, and each scene has its own date and weather conditions indicated by the phone. However, the minutes on the clock are pulled directly from the clock on the computer running Eliza. I found that you can cause the in-game phone clock to change by changing the time on your computer, and that if the minutes on the phone clock overflow to a new hour, the hour indicated does not change. I think it’s quite unlikely anyone would notice this unless they pull out the phone as the time goes from 1559 to 1500, but it does happen.

The other kind of gameplay is Eliza sessions, where Evelyn acts as the proxy between Eliza and a client. The player is given a HUD with some biometric information about the client, conveyed to Evelyn by augment reality glasses, that has no practical utility. There is no point where monitoring the clients heart rate or vocal waveform informs the session for the proxy – as Evelyn herself calls out, this is set-dressing to improve the experience for the proxy (and the player) by slapping on a sci-fi aesthetic onto the therapy session. This is the most akin to a radio play – there are no dialogue options as proxies are not allowed to go off-script (and you’re not allowed to whip out your phone). The only exception for this is in the last chapter, where the player can choose to have Evelyn speak directly to the client instead of saying the prompt from Eliza. This is very much intentional as Burns says in his Q&A: “As the game itself acknowledges very early on, sometimes you don’t have a choice… my hope is that then when the choice does actually appear it’s very dramatic and meaningful because, because finally you have a choice”. [1] The sessions generally follow the same track up until the end, where Evelyn’s advice seems to have more of a connection with the client than Eliza’s, despite both having similar outcomes for the client. The final twist on the formula is when Evelyn attends an Eliza session as the client. This is the puzzle piece letting the player, and Evelyn, fully understand what an Eliza session is. It also helps mark the point at which Evelyn is defining her own life again, rather than being pushed along by the tide.

Eliza sessions follows a set format. Using the first session in the game as an example, first is the introduction phase where Eliza puts the client at ease by making some small talk:

“Hope you didn’t get rained on too much.”

Following this is discovery, where Eliza invites the client to discuss their problems:

“Do you remember anything in particular that caused these feelings?”

Then is the challenge phase, where Eliza uses leading questions and comments to have the client reflect on their current situation and possible resolutions:

“Would you be happy if you had those things too?”

Finally is the intervention, where Eliza suggests a treatment plan. This is typically some wellness exercises in the Skandha Wellness app and/or medication:

“First, I’m going to send a set of breathing exercises for you to do.”

Evelyn typically reflects on the session after its conclusion, and may discuss it with one of the core cast. For example, the first session with Darren Willows is one of the most intense sessions in the game, after which centre manager Rae talks it over with Evelyn to make sure she’s okay.

At three points you take part in Transparency Mode. Here, an Eliza client has given permission for Eliza to have access to their entire phone, and as the proxy Evelyn has to double-check Eliza’s working by reading their emails and dm’s to gauge their mental state and what’s going on in their life. The gameplay here boils down to answering a handful of yes/no questions, again with no impact on the events of the story. These sessions are highly intrusive, it not being clear if one elderly client really understands what they’ve agreed to and another client opting in with a “I don’t care any more” attitude that really stretches the bounds of informed consent. Either way, Skandha doesn’t care.

There are fourteen sessions in the game, with six clients. An illustrative example is struggling artist Maya Leeds – initially coming for her social anxiety, we see her enthusiasm wane as she is rejected by the Seattle art scene. She becomes less optimistic, finally deciding to quit and become a teacher. I find Maya’s story very grounded and relatable. It’s also a common theme for these sessions that these people are facing complicated issues, for which there are no neat conclusions.

Graphics, Audio, and Music

The music in Eliza is really good. I’m listening to the OST right now; it was composed by Matthew S. Burns, who was also the lead writer for Eliza and appears to have been the main creative force behind the game. I enjoy the variety that is found within the OST, with tracks like “Reflection” using lingering piano keystrokes to impart a sense of calm and space while “Complication” draws from electronic sources to create an ambience akin to being wedged between speakers that are playing lo-fi beats to relax/study to. Within Eliza these tracks are used effectively to set the stage, linking specific tracks with characters or location to inform the player emotionally about the content of the scene before it’s finished playing out. The only two tracks I don’t like are “The Club” and “Nora’s Track” as the muffled distorted filter reminds me of listening to other people’s music through the walls of my undergraduate halls, but they still suit the game. It’s clear that the OST was made with a specific creative vision, and indeed that Burns was the musical mind behind the entire Zachtronics catalogue.

Following on from this, I enjoy the audio design of Eliza in general, particularly the voice acting. The cast is relatively small, and all of the actors give great performances. My stand-outs are Evelyn, for the depth of emotion she’s able to access, and Soren, for how worn out he sounds (you and me both). The general audio design achieves the high standard of being done well enough that I stop noticing it, melding into the background of the game world. I don’t have anything outstanding to highlight, but no notes either.

My slight sadness is the graphics. While very beautifully drawn, they have limited animation. Characters are all drawn in one pose, and may have one or two outfits, but that’s all you get. There is no animation during cutscenes, and very few backdrops have animated elements. I can and will daydream about a version with animated portraits, along the lines of Mask of the Rose where they move between poses, but the variety in background art and the other great audio-visual presentation make up for it. In this timeline, we’re stuck with Eliza the radio-play.

Here ends the Eliza essay. However, I’ve put together some extra words for those interested:

Literature Review

I couldn’t find that much material online about Eliza. That’s why we’re here today, dear reader. The game released on August 12th 2019, and the usual gaming magazines had reviews out around then. I found it interesting that each reviewer chose a different aspect of the game to structure their article around – Jeff Ramos in Polygon focussed on the implications of AI-driven therapy, while Sin Vega in Rock, Paper, Shotgun homed in on the gamification of the therapy experience [2, 3]. The common thread for reviews was praise for the writing, voice-acting, and visuals, then lamenting the lack of animation and the limited choices available to the player [4-6]. An interesting addition is a playthrough and Q&A with Eliza creator Matthew S. Burns [1], where he lays out the inspiration for Eliza and talks about the motivations for making the game. On the community side, there are various let’s plays of Eliza on YouTube (which I did not watch), some material on the Eliza subreddit [7], and one Steam user guide that went so far as to make a flow-chart for all of the dialogue choices available in the game [8].

Despite praise, the wider impact of Eliza has been limited. I was already aware of Jacob Geller’s Fixing My Brain with Automated Therapy, which draws from Eliza to illustrate how a technology-focussed approach to therapy limits and informs what kinds of therapy will be available to clients (as well as the inevitable data privacy issues) [9]. Aside from this I found two academic articles, one briefly mentioning Eliza as an example of a game that doesn’t explore how to change corporate structures from the inside, the other currently trapped behind a paywall [10, 11]. At the time of writing, this is the sum of thought on Eliza that I was able to uncover.

Introducing Eliza the AI

Eliza isn’t strictly about artificial intelligence. Rather, I’d say it is about the intersection of social and personal issues with technology, represented by an AI called Eliza. This is great for me, as we won’t have to delve too deeply into the field of artificial intelligence, which comes with a lot of terminology that I feel makes it difficult to access for the lay audience to parse (including myself). A key feature is that AI is quite loosely defined, essentially being a marketing term for any sufficiently advanced software, rather than referring to either a specific kind of technology like a neural network or a technology for a specific application like large language models used as chat-bots. This means we’re in the clear to call Eliza an AI without worrying about how or why it works. I would like to see someone with more knowledge about AI pick apart Eliza from a technological standpoint, as fun exercise.

A clear inspiration for Eliza is ELIZA, a program from 1964 created to investigate natural language communication between computer and human users. In particular ELIZA was capable of roughly simulating person-centered therapy, taking the role of the psychiatrist. ELIZA essentially asks leading questions or makes open comments based on what the user has said, as seen in the Weizenbaum’s 1964 research paper [12]. Some of the phrasing of Eliza’s Eliza seems to have been taken directly from ELIZA, the phrase

“WHAT WOULD IT MEAN TO YOU IF YOU GOT SOME HELP”

jumping out in particular. Other than historical context, and possibly informing the development of the ideas behind the game, I find ELIZA has little impact on Eliza.

As mentioned above it’s not necessary to speculate how exactly Eliza would work when talking about Eliza, as this doesn’t necessarily affect the interpretation of the events of Eliza. Eliza represents several ideas, like technology intruding on previous human-dominated spheres like therapy and the increasing ubiquitousness of technology in everyday life, and is the catalyst for several other ideas namely; data security, interfacing profit motives with healthcare, the effectiveness of technological solutions to emotional/mental/social problems, and the feeling of having no control over your life. It may disappoint some players that Eliza doesn’t dig into tech-focussed issues like AI alignment, but at its core Eliza is about people – not machines.

References

[1] Eliza Playthrough with Matthew Seiji Burns, Strand Book Store, Youtube, 2019, accessed August 2024.

[2] Eliza explores the dangers on on-demand digital therapy, Jeff Ramos, Polygon, 2019, https://www.polygon.com/reviews/2019/8/12/20798997/eliza-zachtronics-visual-novel-review-impressions

[3] Wot I Think: Eliza, Sin Vega, Rock, Paper, Shotgun, 2019, https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/eliza-review

[4] Eliza review: Startup culture meets sci-fi in a touching, fascinating tale, Sam Machkovech, ars Technica, 2019, https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2019/08/eliza-review-startup-culture-meets-sci-fi-in-a-touching-fascinating-tale/

[5] Eliza Review Maybe Computers Shouldn’t Be Therapists, Jamie Latour, The Gamer, 2019, https://www.thegamer.com/zachtronics-visual-novel-eliza-review/

[6] Eliza – Review – A strange Visual Novel about AI controlled therapy from Zachtronics, Kinglink Reivews, YouTube, 2019.

[7] r/Eliza, Reddit, 2019, https://www.reddit.com/r/Eliza/, accessed August 2024.

[8] Choices, Outcomes, and Endings, CyberShadow, Steam, 2019, https://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=1833865162

[9] Fixing My Brain with Automated Therapy, Jacob Geller, YouTube, 2022.

[10] Playing the Belly of the Beast: Games for Learning Strategic Thinking in Tech Ethics, Aditya Anupam, Information Medium, and Society: Journal of Publishing Studies, 17-32, 2024, https://doi.org/10.33063/ijrp.vi13.307

[11] Eliza: Lessons from Interactive Novels about Publishing in the Era of AI, Dora Kourkoulou, 10.18848/2691-1507/CGP/v21i02/17-32

[12] Weizenbaum, Joseph "ELIZA – A Computer Program For the Study of Natural Language Communication Between Man and Machine" in: Communications of the ACM; Volume 9 , Issue 1 (January 1966): p 36-45.

This work is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0