Seeking Immortality in Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice

Reading Time: 30 - 40 mins

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Authorial Limitations

Story Content and Mechanics

The Headless

The Infested Monks

The Palace Nobles

The Divine Dragon

Killing Immortal Beings

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Foreword

This essay is a bit of an odd one. It’s been about a year in the making and through several permutations, each time increasing in length and complexity. The main person I wrote this for was myself, as something to do on long train rides, and it stemmed from how much I love playing Sekiro. I’m no longer sure if anyone wants to read several thousand words on how I interpret the presentation of immortal side-characters in Sekiro but I know if I don’t kick it out the door it will keep growing, spreading like the Dragon Rot as it eats into my other projects. - BLW

I enjoy reading Ben’s writing. His scientific writing, I had been reading for several years now. This essay on Sekiro was the first I’d seen on a non-scientific topic. I felt that others would appreciate his thoughts as much as I do, and that’s how we ended up with Signal Decay. I just really wanted to see what I considered excellent analytical and critical writing published somewhere. - L

Introduction

For FromSoftware, immortality leads to suffering. Their games typically show societies and individuals that have been ravaged by an inability to die, a theme core to the Dark Souls games in particular. A key aspect in these games is that the death and resurrection of the player is given a narrative explanation; typically the player characters have extreme longevity or the ability to resurrect after death. FromSoftware’s 2019 release Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice (hereafter Sekiro) is rife with characters and groups seeking immortality, and displays the terrible consequences of achieving immortality.

Immortality should be easy to define: cannot die. For me, the issue is being able to prove that someone who is immortal will ‘never’ die. Even if they live a thousand years, that does not guarantee their continued longevity. This means we have to employ a looser definition of immortal in the context of Sekiro: supernaturally enhanced lifespans, extreme longevity, and often extreme resilience and/or the ability to come back to life after death, but able to be killed with the right tools. In this loose definition I also include the undead, both corporeal and ghostly. ‘Supernatural’ can be understood to be a magical or divine source, but of course the real source of immortality is authorial intent.

So why go to the trouble of looking into immortality in Sekiro? I feel like immortality is a large part of the game, but discourse about Sekiro tends to gloss over it in favour of focussing on the big events of the story or the gameplay. While present throughout the game, immortality is often lurking just below the surface or is not directly addressed. Hopefully this discussion provides food for thought and encourages others to take a closer look at eternal life in Sekiro.

Authorial Limitations

Firstly I need to acknowledge some key limitations in this essay. I, the author (hello), do not speak or read Japanese. I played Sekiro with English subtitles/translations and the original Japanese audio. This leads into the inescapable issue that discussing Japanese culture in English can lead to misunderstanding or confusion based on the exact translations used. I have made an effort to seek out alternative translations of names and locations in Sekiro to those presented in the game, in order to find any allusions that may have been lost during localisation. Sekiro is rooted firmly in Japanese culture in a historical context, and contains substantial elements of and references to Buddhism, Shinto, and Japanese folklore.1 The precise terminology used to discuss these topics is important as it can colour the views of the reader. Terminology in Sekiro will be discussed using both the official English translation, and using a “literal” translation of the official Japanese version of the game where applicable. It should also be noted that despite the best efforts of the author, this essay fundamentally represents a Eurocentric view of Sekiro. While an attempt has been made to put Sekiro in the appropriate cultural and historical context, this can only scratch the surface of the context and allusions available in Sekiro for a player who is not an outsider to Japanese culture and Japanese history.

Story Context and Mechanics

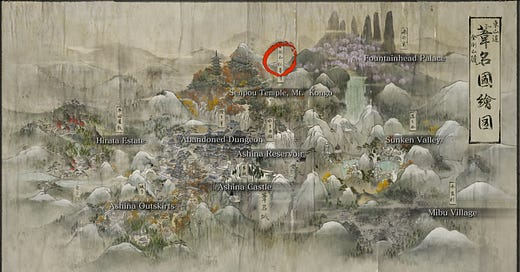

I will briefly recap the essential story and mechanics of Sekiro, but if you are familiar with the game then you might want to jump ahead to the next section. A good summary is also given in the YouTube video essay by Jacob Geller. In Sekiro, the player is cast as Ōkami (also known as Sekiro), a shinobi in Sengoku era Japan (~1467-1615). Ōkami is in the service of Kuro, a boy with immortality of supernatural origins. The game takes place in Ashina province, a fictional area of Japan dominated by mountains and valleys. At the start of the game Kuro has been kidnapped by Genichiro, the current ruler of Ashina. Genichiro intends to use Kuro’s innate power of immortality (the Dragon’s Heritage) to make Ashina impervious to invasion. During the prologue it is revealed that Ōkami has received the ability to resurrect from Kuro, meaning each time Ōkami is killed it is a minor setback. If this seems like a lot of details all at once, let them wash over you and refer back here if you get lost later on.

The basic combat mechanics and the respawn systems of Sekiro are worth going over as they are how the player experiences the game. The essential details will be familiar to anyone who has played Dark Souls or Bloodbourne, with some key differences. The player can rest at a Sculptor’s Idol to restore their health, which will repopulate the game world with all enemies the player has killed (with the exception of bosses and mini-bosses). This respawning is not presented as immortality in Sekiro, and can be considered a mechanical concession to the narrative that creates a gameplay challenge. Bosses and mini-bosses die permanently when killed, which progresses the story to the next set of bosses. If the player is killed they can spend a node of Resurrective Power to come back to life, or they can die and respawn at a Sculptors Idol. If the player dies repeatedly, an effect called the Dragon Rot is triggered. The Dragon Rot is a fictional illness in Sekiro caused by the player character’s resurrections draining the life force of the friendly NPCs. Until the player cures their Dragon Rot, their quests cannot be progressed. These mechanics are how the player will experience much of their moment-to-moment experience with Sekiro, and they begin to convey the message that immortality in Sekiro is a damaging process for the immortal being. Cheating death does not benefit the player other than giving them multiple chances to beat a difficult fight. Dying is a setback; indeed deathless runs of Sekiro are possible in part due to there being no real advantage to dying.

The Headless

The player can meet an immortal foe early in their play-through if they encounter a series of ghostly mini-bosses – the Headless. These are a collection of yūrei that were created when great warriors from Ashina were beheaded and their bodies discarded without burial (Figure 1). Yūrei are the souls or essence of a dead human that lingers in the world around the place of their death. Yūrei often arise due to improper burial or unwillingness for a soul to leave the living world, and may have great resentment towards the living (Kazuhiko 135). The Headless now haunt the site of their deaths in Ashina, and manifest their hatred of the living by killing anyone who approaches them.

The visual design of the Headless evokes a walking corpse, incorporating touchstones for sickness like pale clammy skin. They have no head, with a raw red neck stump betraying their beheading. The Headless do not speak, indeed they lack a tongue and their vocal chords would have been damaged when their heads were cut off, but while fighting they emit strangled gurgles and gasps. The hands and feet of the Headless are darker coloured than the rest of their body, implying blood has pooled in the limbs after death as though they were standing when algor mortis set in. If they had received a proper burial, they would have been lying down and blood would have pooled in their backs. The Headless are also naked apart from a small cloth at their waist; funeral clothes would have implied that they had been buried with due process and respect, while the Headless were either made to strip before execution or their bodies looted after death. Amidst this it is impossible to miss that each Headless carries a sword wreathed in purple fire which they wield in an otherworldly combat style, more like a dance than fencing. Sekiro is mostly well-grounded in its depiction of sword fighting (more acrobatic moves like the Nightjar Slash notwithstanding), so the unusual fluid movements of the Headless and their fiery weapons mark them out as unusual and dangerous.

The Headless are accompanied by a series of supernatural phenomena that reinforce their otherworldliness. They are wreathed in mist which slows the player down to a walk. This helps fights with the Headless stand out, as this is the only place in the game this mechanic exists, and makes them challenging to defeat. Periodically during a fight the Headless will disappear, fading out of existence, then appear behind the player to execute a grab attack. If successful the Headless places its hand inside Ōkami’s anus and violently removes a small ball, which it then places inside its own anus.2 This sequence is very upsetting; Ōkami is clearly in pain and it represents a major violation of his person. This sequence is commonly accepted as a reference to the shirikodama (by the Sekiro Wiki), a mythical organ housed inside the anus that contains the spirit or soul.3 This scene can be read as the Headless literally ripping the soul out of Ōkami, which it may be doing in an attempt to restore itself to life, or simply to punish Ōkami for disturbing the Headless.

There are five Headless in Sekiro. The first the player is likely to encounter is in a pitch-black cave, with the others in equally out-of-the-way location like the bottom of an overgrown valley or in the Ashina Castle moat. The key link between these areas that elevates them beyond mere combat arenas is that the Headless have been abandoned out of sight, with the player having to work hard to find them. The rulers of Ashina clearly fear the Headless, seen in their unwillingness to build them burial mounds, and their solution has been to avoid them as they are unable to drive them away. This is shown with a note the player can find near the Headless in Ashina Outskirts, reading:

“Turn back if you value your life. You can’t behead the headless. Our swords and pikes did nothing.”

Although the Headless are aggressive toward the player, the Headless make no effort to seek out Ōkami. If the player avoids them, the Headless will continue to exist standing in place. This may be a mechanical concession to stop the Headless hunting down the player, but considered as a story element it shows that the Headless linger about the place of their death. While it is easy to consider the Headless along the lines of a vengeful undead haunting Ashina, on closer analysis the Headless seem more deserving of the player’s pity. They have an unfulfilling, hollow existence, isolated from the rest of Ashina to which they used to belong. Rather than a malicious haunting, the Headless may be self-consumed with regret at their separation from Ashina and the world of the living. As they cannot communicate, it is left to the player to speculate.

Defeating a Headless grants the player a Spiritfall, an item which grants a combat buff and has some fluff text about the origin of the Headless. The description of Ungo’s Spiritfall reads:

“Fallen, headless spirit of Ungo… Headless are the ruined form of corrupted heroes who once fought for their country. This warrior lost his mind in defence of the state. His attempted mutiny was met with a swift beheading, and the lifeless body sunk to the bottom of the moat.”

The Spiritfalls show that Ungo, and the other Headless,4 met ignoble ends despite their previous service to Ashina. Ungo’s body in particular was thrown into the moat of Ashina Castle. In death they have been rejected by their old comrades and superiors via the lack of a proper burial, so it is no wonder that they linger as Headless and express anger towards the living by attacking them. Indeed Gokan’s Spiritfall reads “dedicated burial mounds quietly appease the spirits with severed heads,” illustrating that the people of Ashina are not willing to take steps to deal with the Headless.

Overall, I see the Headless as a metaphor for people cast aside once their usefulness is done, whose actions are seen as “violent” despite their having no other recourse for making themselves heard. The Headless have no voice, and no-one is willing to understand their actions. The leadership and people of Ashina would prefer to ignore the Headless so they can live in relative comfort, and rather than appeasing their grievances the Headless are brutally dispatched by the player because they present a threat.

The Infested Monks

Up next is another form of living death, via the Infested monks at Senpou temple. Infestation in Sekiro occurs when, for unknown reasons, parasitic centipedes grow inside the body and resurrect the host upon death as well as extending the lifespan of the victim (Figure 2). Beyond the visceral body horror of having a centipede living inside you, the centipedes in Sekiro may be a reference to centipede yōkai that appear in some Japanese folk tales such as the giant man-eating Ōmukade (Ashkenazi 117).5 The visual design of the centipedes in Sekiro appear to have been inspired by Scolopendra subspinipes, the red-headed centipede. This is a large aggressive species found in Japan, and the centipedes found in the game are equally characterised by their aggression towards the player.

The origin of the centipedes in Sekiro is unclear, but they are present extensively in Senpou Temple, a Buddhist Monastery where the monks have abandoned traditional Buddhism in order to search for eternal life.6 Senpou Temple is located in the mountains of Ashina, and is both remote and difficult to access. This may have contributed to the monks straying from orthodox Japanese Buddhism and becoming obsessed with immortality. In contrast to the Headless, the monks are implied to have chosen to seek immortality and willingly accepted Infestation as a means to an end.

Many of the monks in Senpou are Infested, and now have decaying corpse-like bodies that imply a state of living death similar to that of the Headless. In particular, the player will come across several monks who appear to have died while meditating. These individuals have dried leathery skin and sunken, eyeless sockets in their skulls. Visually these resemble people who have undergone sokushinbutsu, which was the practice of following an extreme ascetic lifestyle that results in the body being preserved as a mummy on death (Fujita et al.).7 These monks have achieved a form of living sokushinbutsu, and now like the Headless they exist eternally in one place. Unlike the Headless some of these individuals are also surrounded by groups of monks, marking them out as objects of veneration. This implies that for the monks of Senpou, Infestation is both desirable and a mark of high status.

In Sekiro, when the player approaches one of these living sokushinbutsu monks, a huge centipede bursts from their body to attack the player. This is a big surprise the first time it happens, and visually disturbing. It’s not entirely clear to what extent the monks are alive, and to what extent they are just a habitat for the centipede. These monks can only be killed using the Mortal Blade; this means when the player first encounters them, they are an unkillable, persistent threat. Despite the centipede having a ranged spit attack and moderate range for melee due to the length of the centipede, these monks are actually not that threatening as an enemy. They are unable to move, and in most cases Ōkami can easily run past them. They are also localised to one part of Senpou Temple, and do not represent a reoccurring threat. Like the Headless, these monks can be avoided and left to their eternal existence if the player chooses.

Senpou Temple itself is in a state of advanced decay. The interior of buildings are filthy and covered in cobwebs, with some infested with aggressive crickets. The stone tiled floors are cracked with pieces missing, and little natural light penetrates the interior spaces. Elsewhere plants are overgrowing the paths of the temple grounds, and leaves have been allowed to pile up on the verandas of buildings. The one part in good repair are the shrines, implying that the monks still follow some of their Buddhist beliefs. Alongside the decay of their physical bodies and their home, the desire for immortality has allowed the monks to justify increasingly violent actions. The player may come across monks meditating in front a shrine, corpses at their feet (Figure 2b). Elsewhere in the temple grounds can be found the bodies of men and women, likely pilgrims or the citizens of Ashina who brought food and supplies to the temple. They have been bound and flung from cliffs, implying that these people have been rudely disposed of when their usefulness to the monks has finished. It seems that whatever the new practices of the monk, they need a steady supply of warm bodies which are dumped in the temple grounds when finished with.

My interpretation of the monks’ motives is speculative, as I do not have a background in Buddhism or theology. The monks may view extreme longevity as a way to achieve nirvāna (Mizuno 132) and escape from saṃsāra, commonly described as the cycle of death and rebirth (Mizuno 25). It may be that the monks consider the “living-sokushinbutsu” monks as having achieved nirvāna while remaining on the earth (Mizuno 133). My tenuous evidence for this is from the Holy Chapter: Infested, an in-game item where an unnamed monk writes “To be undying is to walk the eternal path to enlightenment.” In any case, while Infestation in Sekiro furthers the theme of immortality as a curse and as a sickness through visual design, it is also introduces the corrupting influence of the desire for eternal life on the moral compass and beliefs of those who search for it. For the monks of Senpou Temple immortality is a goal for which the end justifies any means, even though the methods to achieve it are viscerally unpleasant. The monks then act as a warning for seeking to achieve a goal at any cost: success is not certain, and if achieved you might be changed beyond recognition.

The Palace Nobles

The Fountainhead Palace is a ruined and flooded complex atop a great waterfall. It is separate from the rest of Ashina and from the control of the Ashina clan, only reachable in the game after getting a lift from a huge straw doll (it’s a whole thing). This helps set the area apart from the rest of Ashina, and marks it as special. While the first impression is of grandeur the player quickly notices that the Palace is in an advanced state of disrepair. Many buildings have been swept away by the river or sunk, and like Senpou temple the remaining builds are in disrepair. Many have holes in the walls, floors, or roofs; the interior spaces are neglected and poorly lit. This continues the visual design choice of linking immortality to decay seen in Senpou Temple, taken to the extreme.

The Fountainhead Palace is inhabited by the Palace Nobles. These beings were once human, now transformed into amphibian-like creatures dressed in fine clothes (Figure 3). The Nobles have sunken eyeless sockets and long grey hair that hangs around their head as though damp. The skin of the Nobles is blue-white, appearing at times luminescent or translucent, with glowing blue patches. Many Nobles play a flute with their upper pair of arms, while their lower arms hang relaxed below. The Nobles also have a long dragging tail (Figure 3). For me, this gives the impression of an amphibian such as a newt or axolotl, reinforcing the link of the Nobles immortality to water.8 In Mibu Village, an area reached earlier in the game, the player can encounter the village priest with an unquenchable thirst for sake. If the player brings them the Water of the Palace, an item found at the Fountainhead Palace with the description “A cup filled with divine waters”, the priest will drink it. After resting at an idol the priest will have turned into a Noble, confirming that these beings had a human form once. We can also infer that for at least some of the Nobles, drinking the Divine Waters was an active choice in order to gain immortality. The immortality of the Palace Nobles is not stated explicitly but can be inferred from their strong resemblance to the Divine Dragon, the kami from which the Waters of the Palace stem (Figure 4a). There are hints that the Palace Nobles are not satisfied with their longevity seen in the Pot Nobles, a pair of Nobles the player can interact with during a side quest.

The Pot Nobles are a pair of Palace Nobles who the player meets during the course of the game. One is in the Fountainhead Palace, while the other in the earlier area of Hirata Estate.9 The Pot Nobles are not seen outside of their pots but will extend an arm from within to trade with the player for Treasure Carp Scales, a currency that exists for trading with the Pot Nobles. It is not clear to me why the Pot Nobles are hiding inside of large ceramic jars, although it may represent an egg from which the Nobles will later hatch if the player aids them on their quest to become a giant immortal carp.

Having already given up their human form, the Pot Nobles pursue further transformation into a carp. In dialogue, the Pot Noble at Hirata Estate says that he wishes to become “A giant carp that will keep growing and live a long, long life. A carp that never grows old…”. Clearly the Nobles value long life over the form that life takes, with the Pot Nobles choosing life as a carp as preferable to death. Zullie the Witch pointed out in their YouTube video that a giant carp represents the ultimate goal of immortality for the Nobles, as well a critique. They point out that it could be argued that life as a carp is more restrictive than that of a land-dwelling person, as the carp is trapped in water. From another perspective, a carp in water has more freedom than a land-bound human who is restricted by gravity. The inspiration for the desire to become a carp may stem from The Dragon Gate story originating in China, where carp are transformed into dragons if they can leap up a tall waterfall (Birrell 242). As the Fountainhead Palace is at the top of the waterfall, this reinforces the allusion.

To become a carp, the Pot Nobles have Ōkami poison the giant carp that currently lives in the great lake at the Fountainhead Palace. To do this the player takes Truly Precious Bait from a Pot Noble of their choice and feeds it to the giant carp by ringing a feeding bell, then throwing the bait into the mouth of the carp when it appears. This poisons the carp, killing it. This will cause one Pot Noble to leave their pot, having turned into a large carp, while the other Pot Noble dies. The successful Pot Noble will continue to trade Scales with the player, as they wish to become a bigger carp. If the player swims below the waters of the lake, they can find a skeleton of another giant carp. Taken together, this implies that this is not the first time a carp has been poisoned and replaced, indicating that immortality via carp is not the safe option the Pot Nobles blindly believe it to be. Further, as aiding one Pot Noble to become a carp causes the death of the other this is a competitive option that is not open to all. This shows that while the Pot Noble might have obtained short term safety by becoming a carp, in the long run they could be vulnerable to the same fate.

The Pot Nobles are summed up well by a quote from a tarot card found in an unrelated game, the Zachtronics Solitaire Collection: “Getting what you wanted didn’t solve anything. It turned out you needed more. Something better. Something different. How long will you keep chasing it?” The Pot Nobles are ostensibly immortal already, but since then they have been unable to enjoy their new life and fixate on how to become an immortal carp. In essence this is an expression of the issue that faces immortal beings. We can assume that becoming a carp will not be the end of their longings, with the possibility that they will one day be killed and replaced by another Noble looking to secure their future. What they thought was a safety net for a long, long life turned out not to be a sure thing. Having already taken a step on the path towards immortality, the Pot Nobles have no trouble taking another, and another, and another…

The Divine Dragon

The Waters of the Palace made reference to divinity, and were a hint to the ultimate source of immortality for the Palace Nobles; the Divine Dragon, a kami linked to the river that flows though Ashina (Figure 4a). Kami is often translated as a deity or a spirit, or a powerful force in nature, and here represents a powerful being associated with a particular feature of the landscape such as a river (Humphreys and March 178). A player unfamiliar with Japanese dragons may interpret the Divine Dragon as a monster that guards immortality in line with the trope where a dragon is a beast that guards a treasure hoard. However, as a kami the Divine Dragon is instead a physical embodiment of the river.10

The Divine Dragon is found in the Divine Realm, accessed by following the river flowing through the Fountainhead Palace to its source. There, in a cave, the player finds a shrine at which Ōkami can meditate. This transports him to the Divine Realm, which mechanically speaking is a boss arena for the Divine Dragon. The transportation is interpreted as literal as Ōkami bring his weapons with him and leaves with a physical object, the Divine Dragon’s Tears. The immortality of Ōkami ultimately derives from the Divine Dragon, as it is the source of Kuro’s Dragon’s Heritage. Mentioned in the mechanics section, Ōkami’s deaths trigger the Dragon Rot debuff, an illness characterised by difficulty breathing and a hacking cough. The spread of this sickness in Ashina is mirrored in the Divine Realm, through the Old Dragons of the Tree. These are beings with a human face, but a body that is cross between a serpent and a tree (Figure 4b). This is a visual link to Divine Dragon itself, which has a long serpentine body that seems to be part of the sakura tree from which it emerges. Zullie the Witch gives a good breakdown of the design of the Divine Dragon in their video. The Old Dragons of the Tree move slowly and cough a damaging green mist reminiscent of bile, much as the victims of Dragon Rot can cough up blood. As the Divine Dragon does not appear until Ōkami has killed all of the Old Dragons, we can intuit that the Old Dragons are a representation of sickness afflicting the Divine Dragon. As suggested by Zullie the Witch’s video, killing the Old Dragons then represents cutting dead wood from a tree, restoring the Divine Dragon to health. This further shows that mortals using the essence of the Divine Dragon to cheat death, either through the Dragon’s Heritage or by becoming a Palace Noble, is weakening the kami. This allusion is strengthened by the visual resemblance of the Palace Nobles to both the Divine Dragon and the Old Dragon of the Tree, indicating that their transformation stems from the kami.

The Divine Dragon reinforces the idea that immortality in Sekiro comes at a cost. While touched on by the Headless and Senpou Temple the Divine Dragon directly confronts the player with this via having them fight the Old Dragons of the Tree who both look like the Palace Nobles the player has recently confronted, and whose banishment restores the Divine Dragon to full strength. In essence, immortality is presented as a finite resource that has been abused by both the people of Ashina and the player, leading to the loss of health of the Divine Dragon and the spreading of the Dragon Rot sickness. This shows the player that exploiting the resource of immortality can give short-term benefits for the individual as longevity, but the long-term consequence are sickness and death in those surrounding them.

Killing Immortal Beings

The immortal beings the player comes into contact with in Sekiro are usually foes to be defeated in combat. At its core Sekiro is a 3D fighting game about engaging dangerous foes in combat. The game embraces this by making its immortal foes either difficult to fight, or requiring special weapons to be defeated: the red and black Mortal Blades, a pair of ancient odachi.11 The red Mortal Blade wielded by Ōkami is called Fushigiri in Japanese, which can be translated very roughly as “to cut immortality”. This accurately describes the use of the blade by the player. The black Mortal Blade is wielded by the antagonist Genichiro, and is called Kaimon. This can be translated as “open gate” which is a reference to its ability to resurrect the dead (and if you haven’t played Sekiro, you’ll never guess how the player finds this out). I think the colours of the mortal blades reinforce their roles. For Eurocentric players such as myself black can be a morbid shade associated with death and mortality, while red can be an angry colour linked to the bloodshed caused by the blade.

If Sekiro presents immortal beings using visual cues that invoke sickness, the Mortal Blades represent the cure. The unfortunate reality is that the only way to remove immortality in Ashina is via violent death. The deathblow animations involving Fushigiri are uniformly brutal, such as Ōkami using it to tear a giant centipede out of the body of multiple bosses, with it being shown that Ōkami needs to exert great force to draw the blade through the body of his victim. It is not an option for the cause of immortality to be painlessly removed, and the patient to die peacefully of natural causes. This implies that the immortals in Sekiro, even if not killed by the player, will continue to live until someone brings them to a bloody end.

Conclusion

First off, thanks and well done for getting this far. I know it’s been a long one. This essay has rambled around the presentation of immortality to the player at various points during Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice. Throughout, the player can see immortality depicted visually using indication for sickness to indicate that it is pretty bad for the immortal individual. Isolation and abandonment are presented via the Headless, while the Senpou monks and Palace Nobles show that immortality leads to stagnation and does not satisfy the impulse that led them to seek immortality out. The Divine Dragon shows the player the result of their own abuse of immortality throughout the game, spreading Dragon Rot sickness amongst the NPCs and causing the kami itself to become sick. Overall Sekiro questions the assumption that immortality should be attained, showing the player that it will be a curse for the immortal being in the long-term. Treating immortality in Sekiro figuratively, the player is shown that seeking power and immortality can lead to death, despair, and damage in the long-term, both for the seeker and for those around them. This is especially true when these ideas are sought at all costs, without regard for those around the seeker.

I’ve only scratched the surface of Sekiro, and the absence of characters like Isshin Ashina, Genichiro, or Emma probably shines like a beacon to those who have played Sekiro. To do justice to all the characters,12 locations,13 and mechanics would require this essay to be a book. I am unlikely to revisit Sekiro at a future date, so I hope that others delve deeper into the narrative and presentation of Sekiro to really unpick the substance of the game for people to appreciate it more comprehensively.

Acknowledgments

M. P. Weare, K. L. Y. Fung, R. S. Z. Whitehead.

Bibliography

This essay required a lot of research and wouldn’t have been possible without the community wiki(s) in particular, which was invaluable for double-checking details and spellings of names.

Videos

Sekiro’s Parry and Other Pursuits of Perfection, Jacob Geller, YouTube, 2022.

The divine dragon might be dying?, Zullie the Witch, YouTube, 2022.

I can’t tell if it’s lore or just weird programming, Zullie the Witch, YouTube, 2022.

What’s inside the pot merchant’s pot?, Zullie the Witch, YouTube, 2022.

The giant fish has a human face, Zullie the Witch, YouTube, 2022.

Works about Sekiro

Sekiro Wiki, Accessed August 2023.

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice Wiki, Accessed August 2023.

Jaworowicz-Zimny, Aleksandra. ‘Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice and Contents Tourism in Aizu-Wakamatsu’. War as Entertainment and Contents Tourism in Japan, by Takayoshi Yamamura and Philip Seaton, 1st ed., Routledge, 2022, pp. 32–36. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003239970-5.

McWhertor, Michael. Sekiro Is Brutal, Beautiful, and FromSoftware’s Friendliest Game Yet. 6 Mar. 2019, https://www.polygon.com/2019/3/6/18253125/sekiro-shadows-die-twice-preview-impressions.

Thiparpakul, Poom, et al. ‘The Satisfaction of Sword’s Sound Effect in Game Design in Case of Metal Gear Rising and Sekiro: Shadow Dies Twice’. Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Conference on Information and Education Technology, ACM, 2020, pp. 252–56. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1145/3395245.3396406.

Tyrrel, Brandin. Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice Review. 21 Mar. 2019, https://www.ign.com/articles/2019/03/21/sekiro-shadows-die-twice-review.

Genovesi, Matteo. ‘I Passed Away, but I Can Live Again: The Narrative Contextualization of Death in Dead Cells and Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice’. Acta Ludologica, no. 2, pp. 32–41.

Guzsvinecz, Tibor. ‘The Correlation between Positive Reviews, Playtime, Design and Game Mechanics in Souls-like Role-Playing Video Games’. Multimedia Tools and Applications, vol. 82, no. 3, Jan. 2023, pp. 4641–70. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-12308-1.

Works about Japanese Culture, History, and Folklore

Ashkenazi, Michael. Handbook of Japanese Mythology. ABC-CLIO, 2003.

Birrell, Anne. Chinese Mythology An Introduction. John Hopkins University Press, 1993.

Breen, John, and Mark Teeuwen. A New History of Shinto. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Fujita, Hisashi, et al. ‘Mummies in Japan’. The Handbook of Mummy Studies, edited by Dong Hoon Shin and Raffaella Bianucci, Springer Singapore, 2021, pp. 1–14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1614-6_31-2.

Kazuhiko, Komatsu. An Introduction to Yokai Culture: Monsters, Ghosts, and Outsiders in Japanese History. Japanese Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, 2017.

Nara, Hiroshi. Inexorable modernity: Japan's grappling with modernity in the arts, Lexington Books, 2007.

Works about Buddhism

Humphreys, Christmas, and Arthur Charles March. A Popular Dictionary of Buddhism. 1st paperback ed, Curzon Press, 1984.

Mizuno, Kooigen. Essentials of Buddhism: Basic Terminology and Concepts of Buddhist Philosophy and Practice. Koosei Publishing, 1996.

Various literature about videogame studies

Carr, Diane. ‘Methodology, Representation, and Games’. Games and Culture, vol. 14, no. 7–8, Nov. 2019, pp. 707–23. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412017728641.

Ensslin, Astrid. Literary Gaming. The MIT Press, 2014.

Pugachev, Andrei A. ‘Analysis of Russian and Global Game Studies: Ludology vs. Narratology’. RUDN Journal of Studies in Literature and Journalism, vol. 27, no. 4, Dec. 2022, pp. 823–32. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.22363/2312-9220-2022-27-4-823-832.

Warpefelt, Henrik. ‘A Gap in Games Research: Reflecting on Two Camps and a Bridge’. FDG ’22: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, ACM, 2022, pp. 1–4. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1145/3555858.3555916.

Works about immortality in fiction

Botelho, Teresa. ‘The Cure for Death: Fantasies of Longevity in and Immortality in Speculative Fiction’. Intelligence, Creativity, and Fantasy, 1st ed., Taylor and Francis, 2019, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781000734065.

This work is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

My reading suggests that scholars are divided over whether to classify Shinto as an organised religion or a religion at all, in modern and historical contexts. This is further complicated by the term religion in English being Eurocentric and relating the topic back to European Christianity. This can unintentionally encourage the classification of Shinto and Japanese Buddhism along the same lines as European Christianity, which is both unfair and unhelpful (Breen and Teeuwen 7).

I would like to commend FromSoftware for designing a grab attack that is really difficult to discuss in polite company.

The only information about shirokodama I could find was in relation to kappa, an aquatic yōkai. Kappa were said to steal the shirokodama from people as well as drown people who strayed too near to rivers or lakes (Nara 33). Kappa don’t make an appearance in Sekiro to my knowledge, and the Headless do not resemble kappa in the slightest.

The names of the Headless are: Ako, Gokan, Gachiin, Ungo, and Yashariku.

Yōkai are inhuman creatures appearing in stories. They may exist to provide an explanation for strange or mysterious occurances (Kazuhiko 10).

The beliefs of the Senpou monks are not explicitly stated in Sekiro to my knowledge. I am under the impression that they started as a Buddhist monastery, but I may have missed some details pointing towards Shugendō practices for example. I am also assuming that the monastery conformed to orthodox Japanese Buddhism before they got mixed up with centipedes, but if there is any evidence to the contrary then I missed it. If anyone can shine some light on this, please do.

Sokuhinbutsu is a topic in itself, involving the intersection of cultural and religious beliefs. I’d love to see an expert’s views on this as it pertains to Sekiro, but for myself the monks visual design happens to remind me of the topic.

If the design of the Palace Nobles refers to a specific element of folklore, or to a specific animal, then I missed it.

The names of the Pot Nobles are Koremori and Harunaga.

We can infer this from the language used to describe the dragon; in Japanese, the Divine Dragon is referred to as the Sakura Dragon (桜竜), where ryū (竜) derives from Chinese and refers to “Japanese dragons”; had this been rendered as katakana doragon (ドラゴン), this would imply that the developers intended the Divine Dragon to be interpreted not as a kami. In previous FromSoftware game Dark Souls, which contains exclusively “European dragons”, dragon is rendered both as ryū and doragon. Therefore we can assume that the choice of ryū in Sekiro is intentional and confirms that the Divine Dragon is intended to be viewed as a kami instead of a beast.

An odachi is a sword larger than a katana. An example is the weapon used by Kikuchiyo in the 1954 movie Seven Samurai.

I feel that for characters like Hanbei the Undying, the Corrupted Monk, and the Guardian Ape, immortality (through infestation) has robbed them of their purpose in life. Hanbei is a samurai who wishes to die in combat but cannot. The Corrupted Monk was integral to the Fountainhead Palace, and now guards the ruins and manifests their lack of purpose as violence towards the player. The Guardian Ape seems to be the last of its kind in Ashina, tending a flower to attract a mate that will never come. Each of these characters wears an air of loneliness as they suffer their endless existence.

I do have a few thoughts on Mibu Village, as an aside. The villagers, transformed into shambling grey-skinned husks who rise again from the earth if killed, remind me of the monks in Senpou Temple. Like the temple, Mibu Village has fallen into disrepair as the undying inhabitants no longer upkeep their homes. The current state of Mibu Village seems to be linked to drinking sake supplied by the village priest, which gives them an unquenchable thirst before transforming them. This thirst seems to me to embody the desire for immortality in spite of the harsh physical consequences. I also think there might be something in the villagers having been tricked into partaking of sake, as opposed to the other beings in Sekiro that seek out transformation; and I note for posterity that consuming liquids like water or sake reoccur as the mechanism for longevity throughout Sekiro.